Before Lincoln opened, our administration reached out to stakeholders and members of the community to ask what they wanted Lincoln graduates to walk away with.

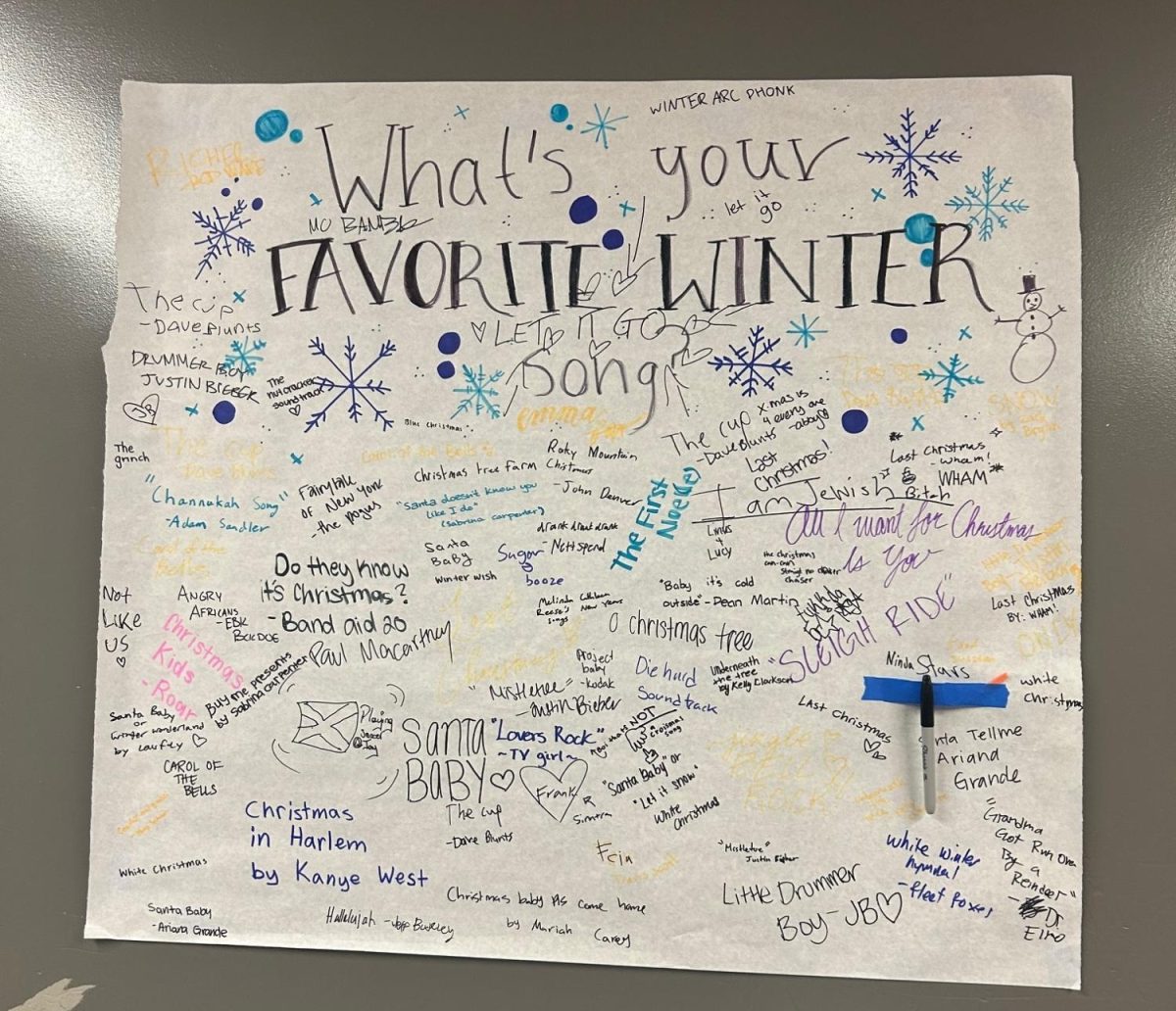

The results were represented as a word cloud, with the largest words being ‘creative’, ‘confident’, ‘college’, and ‘thinker’. The admin started to wonder if the typical high school model would be able to encapsulate each of these goals. So, they looked into alternative methods of teaching, such as Project Based Learning (PBL).

In building this school, Lincoln’s admin combined the Stanford design model, Sustainable Development Goals, 21st century skills, and Social Emotional Learning to embrace a new method of teaching. They hired a PBL consultant, started visiting existing PBL schools, and assembled a team of teachers and students to reach these goals.

As a senior at Lincoln, I became curious about our identification as a PBL school. In creating a school from the ground up, many compromises have had to be made, leaving us in a unique limbo between full PBL and ‘normal’ high school. Sure, we do more projects than most high schools, but if we’re still being assigned final exams, how much of a ‘project based’ school can we be?

Lincoln has had to face many challenges that other PBL schools don’t. Because Lincoln is a public school, enrollment numbers aren’t as limited. Most PBL schools have much smaller student populations, typically hovering at about 200-300, one-sixth of Lincolns population, which makes it much easier to have the personal approach that PBL schools rely on.

Being a public school also means being restricted to public school funding and expectations. Classes and curriculum that aren’t specialized to Lincoln but rather have state or national standards that restrict how much of a PBL approach teachers can take.

It is also clear that the values and systems of the broader country have permeated our school. Having one of the largest words in the word cloud be ‘college’ shows how many parents think of it as the end goal, limiting students ability to plan for other postsecondary options. This often creates the wrong type of motivation for students.

Instead of encouraging them to be passionate about their learning, it encourages students to game the system to get 4.0’s, and take lots of APs, not to focus on their learning. PBL’s capacity to help students is limited by the learning environment and expectations around the country, and how students feel they need to be striving for that.

While there is still a disconnect in many students minds between joy and learning, teachers have remained incredibly driven to uphold their commitment to PBL.

When you apply to teach at Lincoln, a part of the interview process requires you to bring a project that you’ve created that you could teach your classes. This up-front commitment to PBL has cultivated a unique staff of those who are willing to go the extra mile to provide the best education they can, an education that students value.

Activities Coordinator and Leadership teacher Ms. Goehring shared why she wanted to work at a PBL school, instead of a traditional one, saying, “I was feeling pretty defeated by the world of education, and thinking there was no way it was ever going to change.” She felt that Lincoln was the change she needed.

Project Based Learning is incredibly time intensive for teachers. It’s implementation takes a lot of excess planning and unpaid work time, especially when they are working to create projects that they can tailor to the different interests and strengths of Lincoln students.

When asked why they were willing to put in so much extra work for their students, and why they cared enough to work at a PBL school, our teachers responses were full of positivity. Teachers shared that they wanted to give students the opportunity to think about education in a different way.

“It completely flips the classroom and flips the mentality, where the kids see there’s a benefit in learning something, and they know why it’s connected to what they’re doing,” shared Astronomy and Chem/Phys teacher Mr. Bess.

We’ve seen that Lincoln’s staff are working hard and are proudly committed to the idea of PBL, but how is the PBL curriculum affecting students? It’s time that we return to that one word on the word cloud: college.

Have recent Lincoln graduates felt prepared for college upon graduating?

At larger universities, students have found that the PBL approach, on the whole, hasn’t been all that helpful. While certain lessons from specific classes (such as learning how to sequence DNA in Genome Science) have been helpful, many large universities don’t have the same PBL approach.

A struggle that multiple graduates cited in switching from Lincoln to college was how difficult it was to learn how to study for and take tests. Hazel Nowbar (‘23) shared, “For tests in college, project based learning didn’t help at all.”

The biggest part of PBL is that it’s human based and that teachers working to connect with what each student wants and needs. If you go to a larger university, particularly before you choose your major, you will find yourself in large classes in which you may be shocked by the volume of tests and lack of access to your professors.

However, when graduates have had the opportunity to work on projects (particularly ones in which they have more freedom in which direction they go), PBL has made them more confident in their abilities.

Nowbar also mentioned a way in which she felt learning at Lincoln was beneficial to her. “[PBL] made school more interesting to me, because I got to choose what I was studying, and [that] made it more engaging and personalized”.

Having a project based learning approach helps create more organic learning, and helps reduce some of the stress of tests, as it shows them that putting in effort, and engaging in your work, is the most important thing. It teaches students how to communicate and collaborate with others more effectively, to lead a team and stay organized, and to feel more comfortable in presenting and public speaking.

So, is our attempt at PBL good enough?

Currently, the PBL style is being carried out better in some classes than others, with some using projects to prop up the idea of PBL and others genuinely creating them as the main style of learning. Having the style of PBL be inconsistent across classes is okay — some are better crafted for PBL than others — but we have to be able to admit to ourselves that some courses just may not be made for PBL.

PBL can help you find clarity in what you want to pursue post high school, and in the things that interest you in life. That is, if you do it properly and put in the work. We have to ask ourselves, “How much work am I willing to put into my classes? Do I actively want to attend a PBL school?”

Lincolns’ staff, alumni, and current students all share a general sense of care towards Lincoln and the Lincoln community (even with the difficulties in making this school PBL). As Clara Orozco (‘26) said:

“I think in a way, it’s made us closer as a school, just because we’re collaborating with our peers and we’re talking. We’re not just sitting in a class for six hours, doing worksheets by ourselves, we’re talking to each other, sharing ideas, we’re trying to figure stuff out, and problem solving. I think that as a school it’s pretty cool that we can do that.”

Categories:

PBL Is Trying Its Best – But Is It Good Enough?

0

More to Discover

About the Contributor

Áine Morrissey, Staff Writer

Aine is a current senior who is in her 3rd semester with the Lincoln Log. She enjoys learning about science and languages in school, and likes to swim, read, and crochet in her time outside of school. One thing she has been passionate about during her time with the Lincoln Log is a legacy project – the establishment of a subscription service for the Log that will hopefully be passed down to future generations of Lincoln journalists.