PTSA Funding: Providing Essential Services or Exacerbating Inequity?

February 17, 2023

Lincoln’s swim team has been able to purchase “every piece of equipment that I ever thought I would need,” says head coach and science teacher Mr. Kastl.

At Cleveland High School, where Mr. Kastl previously taught and coached, this was far from the truth. “We didn’t have a pot of money to give equipment to kids,” he shared, adding that if a student couldn’t afford to buy a swimsuit, he would typically buy it for them out of his own salary, something that happened every season. There was no financial support.

In Seattle, public schools are mainly funded in three ways: first, state and local levy dollars are allocated based on school population size. Second, federal programs like Title I specifically help schools with high percentages of children from low-income families. Finally, grants and other local programs are available to schools that qualify.

If this system was working according to plan, schools like Cleveland, that have a higher percentage of low-income students, would have more funding available than Lincoln would. So where did the money come from to buy swim uniforms at Lincoln and not at Cleveland? The answer is fundraising, often through Lincoln’s PTSA, or Parent Teacher Student Association.

At Lincoln, PTSA funds are used to purchase everything from tutors to school supplies to library books. In fact, the PTSA has given the library $10,000 every year, adding to the $2,000 allocated from state funding to bring the total to $12,000.

That’s enough for 500 new books each year to keep our library up to date, according to school librarian Ms. Scott. Until this year, when the district allocated additional library funding for low-income schools, some schools had zero dollars annually to update their libraries, which are older than Lincoln’s and even more in need of funding.

In Seattle, there are enormous disparities in privately raised public school income and assets. A 2018 examination of tax filings by KUOW (before Lincoln started) found that Roosevelt High School had more than $3 million in assets raised by their PTSA and two other parent/alumni groups, the Roosevelt Foundation and Golden Grads. Ballard and Garfield had almost $800,000 and $700,000 in assets, respectively.

On the other hand, the PTSAs of some schools – such as Cleveland, Rainier Beach, Franklin, and Chief Sealth – don’t have enough assets or make enough income to even file a tax form.

One controversial use of PTSA funds is to pay the salaries of additional staff members. This is done by many Seattle elementary schools, including McGilvra and McDonald, who use PTSA funds to hire staff members like counselors and foreign language specialists. Some high school PTSAs, like Roosevelt, have rejected the idea of using PTSA funds to hire staff members, as stated in a 2018 letter.

School districts, like Bellevue Public Schools, and some cities, including Austin, TX, have also forbidden this practice, citing equity concerns. The Washington State PTA also advises against but does not forbid the practice.

However, it is unclear how this line is drawn. Even if schools do not use PTSA funds to hire staff members directly, if PTSA money is being used to meet other needs, there will be more room in the budget for other things – like hiring staff. For schools with resources, this is hard to resist.

As noted by Ms. Peterson, a Lincoln science teacher and Building Leadership Team member, “no school that I’ve ever been at, in any district, has ever received enough [funding] straight across to buy the teachers that they need.”

The Lincoln PTSA shared that they do not pay for staff salaries. However, “for us to cover something that allows them to cover hiring a teacher… that could be discussed”, one board member shared, adding that this would not be considered an “underhanded way to hire staff on without making it look like we are doing that.” Tutors for the music program are hired by the PTSA, but when asked about classroom teachers, one board member responded emphatically, “not at Lincoln, not at this time, and not with this board.”

Even without additional teachers, the influence of a well-funded PTSA seeps into the school. At Lincoln, this manifests in part as a fully stocked supply room and reimbursements available for classroom supplies. “That’s not something that every school has,” said Ms. Montgomery, a Lincoln social studies teacher and gymnastics coach.

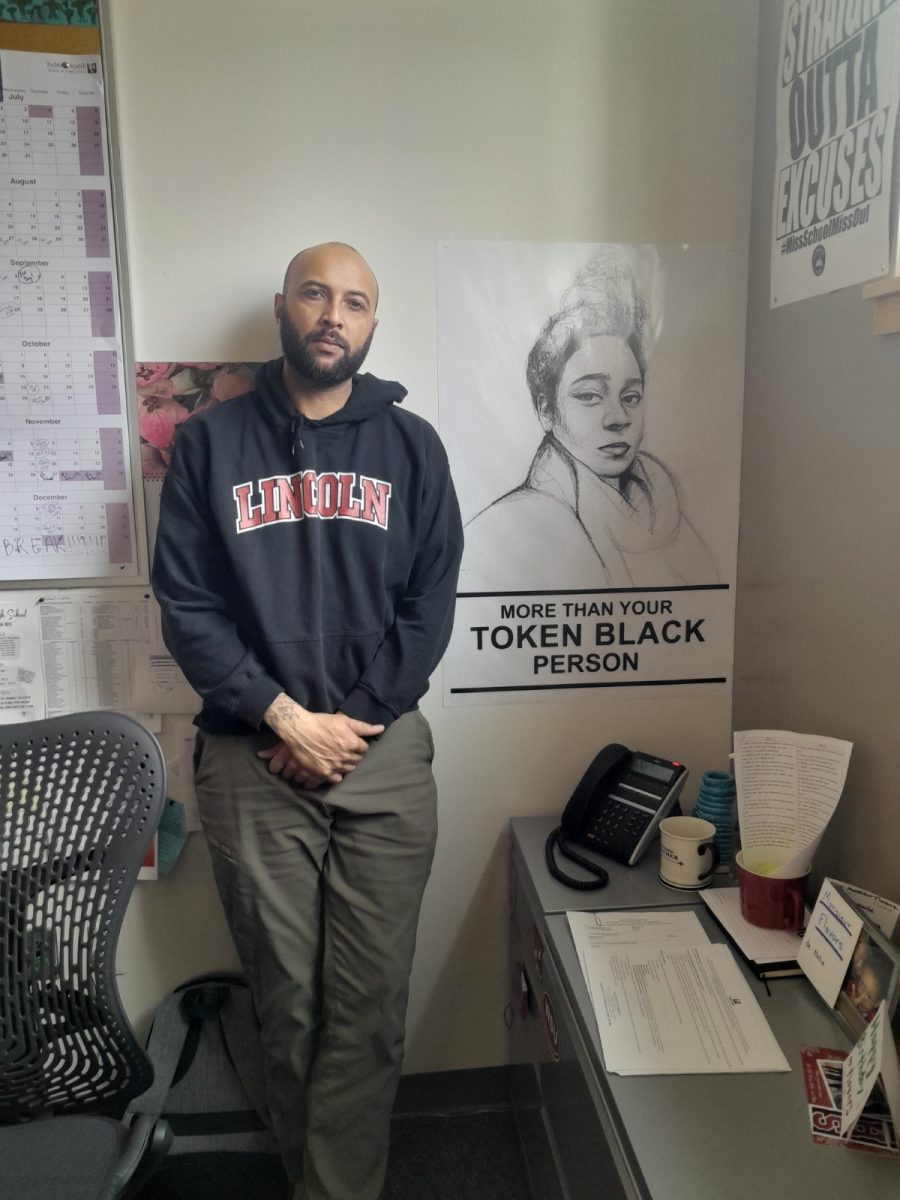

This means that, despite being in the same public school system, schools that serve higher-income students with parents who are able to donate through the PTSA are often able to afford more resources and can offer a higher quality education. In Seattle, with its history of red-lining that effectively segregated some schools, the wealthiest schools have the largest majorities of white students.

FACES (Families and Communities for Equity in Schools), a Seattle non-profit working to change this situation, points to the massive opportunity gap between white students and students of color in Seattle and notes that it has the worst gap in the state and fifth worst in the nation. The fact that the schools with the wealthiest and whitest students can afford more resources is, as they say, grounds for major reform.

Several solutions have been proposed, aimed at equitably re-distributing privately raised funds. One example is the Southeast Seattle Schools Fundraising Alliance, which holds an annual joint move-a-thon fundraiser.

According to the South Seattle Emerald, the 2021 fundraiser brought in over $16,000 for each school involved, which was for some schools more than any past effort. In 2022, the Alliance decided on a new equity-focused formula that equally splits half of the money raised and distributes the remaining half according to a formula that weighs factors including the percentages of students that are BIPOC, English Language Learners, and in Special Education Programs.

The West Seattle Public School Equity Fund is another group working to equitably distribute PTA funds to West Seattle public elementary and K8 schools. Other schools are working on more localized partnerships. In one case, the Greenlake Elementary PTA directs 3% of its funding to the PTA of Rising Star Elementary in South Beacon Hill and sponsors events for the school, a complicated agreement given “concerns of paternalism and white saviorism,” according to Crosscut.

Lincoln’s PTSA hopes to follow a similar path. “We haven’t done something like that yet, mainly because we are a new school, we kind of needed to get things rolling for ourselves first,” one member shared. The PTSA did share some efforts to promote equity inside and outside of Lincoln, like funding $6,000 for ethnic studies classes two years ago and a fundraiser done by the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee that donated $5,000 to “health equity kits” at Rainier Beach High School.

While they are not exactly sure what it would look like, Lincoln’s PTSA has “discussed the idea that our school could [direct] a portion of what we raise towards another school, or that we could have relationships with other schools where there are wish lists or things that we know that they need [that] we are actually helping them purchase with fundraising money.”

Some say that a system where individual schools must decide to pursue equity can never succeed at eliminating disparities, and argue for a district-wide equity fund. One example is the Portland public school system, which switched to a hybrid system in 1995. Individual schools keep 100% of the first $10,000 raised; after that, ⅓ of the donations are pooled in a “Parent Fund”, which is doled out in grants to schools with high percentages of historically underserved and low-income students.

Some Portlanders argue that this is not enough. One group, Reform Portland Public Schools Funding, argues that the current system still allows wealthier, predominantly white-serving schools to unfairly benefit from PTA fundraising disparities, according to a petition that collected over 2,000 signatures. They are pushing for the creation of a district-wide foundation, and argue that this would “[unify] school communities for a common cause” and “[eliminate] racial and socio-economic disparities in the distribution of supplemental funding for staff”.

There is fierce opposition to this idea. One website, Save PPS Foundations, argues that this change would hurt every student and that, without ways to support their children directly, affluent families may simply enroll their children in private schools instead (a practice reminiscent of the mass exodus of wealthy white families to private schools during Seattle’s 1972-1999 school desegregation efforts). They also claim that parents will not donate if at least some of the funds don’t directly benefit their own students.

A 2017 study by the Center for American Progress sought to determine if that was true, examining if Portland’s shift to the hybrid system had decreased the amount of funding raised. They compared Portland to a similar city that didn’t make the same changes – Seattle.

The study found Portland’s equity fund did decrease overall parent contributions slightly, but the benefits outweighed the costs. They concluded that “Portland Public Schools has been able to leverage parent fundraising to benefit its highest-needs schools in ways that Seattle’s most disadvantaged schools do not.”

Even if an equity fund has the potential to work, there are obstacles. The problem is complex, starting with massive wealth disparities and segregated districts, and including parental attitudes, school choices, and an overall lack of education funding. It is clear that Seattle’s current system needs reform.

Here at Lincoln, our PTSA expressed hope to move in the direction of more equitable fundraising, but were unclear if they have the parent support necessary. As one member said, “you need more than just one or two people moving that [forward]. It has got to be a group effort.”

Mariza Cabral (Lincoln parent and DEI member) • Feb 21, 2023 at 10:50 pm

Zoe, Thank you for the excellent article. At a recent General Meeting of the PTSA membership, the DEI committee reiterated its call for the Lincoln PTSA to start sharing funds with less affluent schools. There is also an effort city-wide led by the Southeast Seattle Education Coalition (SESEC). They meet every 3rd Thursday of the month on zoom. I’d be glad to put you in touch if you want to get involved.