Balancing White Guilt in our Schools

June 5, 2023

Our country was built on racism, and despite our efforts to correct this, that foundation still affects us. When I talk about racism in schools with my peers, something I often hear is: “Wow, that happened here? In Seattle?”.

While Seattle may seem like a city mostly free from racism, especially when compared to what you see happening elsewhere on the news, the reality is different. Responding to someone’s personal experiences with racism in places like Seattle disbelief is unfair and counterproductive.

Students’ safety should be a leading factor in educational decision making. However, we cannot rely on our current curriculum to adequately educate students. We are being hurt and hurting others with racist comments, actions, and behavior.

When asked if racism impacted her education, a Black student I interviewed responded: “Yes. In various ways. Sometimes it’s grades, [and] other times it’s the overall experience in the class.

You know, it’s hard to focus in a class where a teacher or other students are saying racist things, and even just knowing you have to be there every day just makes it worse because it can make you feel really helpless. Sometimes you can’t really say anything about it either.”

Our student’s education is causing more harm than good. This student continued to tell me about how the curriculum is incredibly unfair toward students of color. She talked about having to accept a wrong truth in order to get a good grade.

“Especially in history classes, very commonly you have a ‘fact’ told to you. For example, racist laws came before racist ideas and racist hate. Not only is it blatantly incorrect, the examples that teachers try and support these ideas with are even worse. The example used in the case of this idea was slavery.

And as someone descended from slaves, it’s extremely infuriating to have someone say it was just because of laws, when history itself shows that they chose Black people to be slaves because they saw them as less than human.”

This ‘version’ of history is not only inaccurate, but very harmful. As the student says, “It minimizes the harm that was done and outright hides the truth, and for what?

It doesn’t help anyone except for making white people feel less guilty about what their ancestors did, and they’d really rather keep white people comfortable at the cost of hurting black children than just tell the truth.”

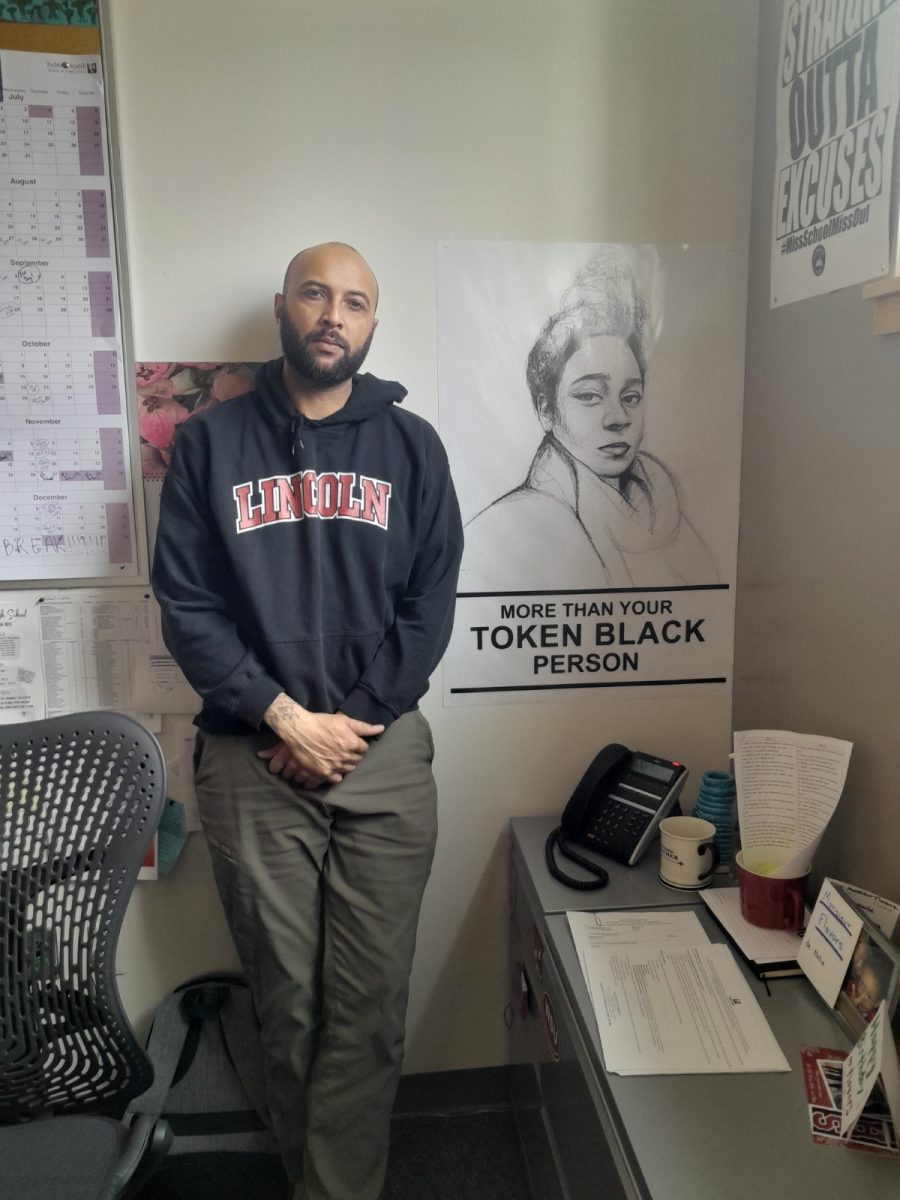

“[The response to racism has been] extremely performative… Pretty much all [of the] ‘antiracism’ is just carried by the Black Student Union (BSU).” It’s not uncommon for students to feel as if the people in charge aren’t pulling their weight.

Every time we have some sort of lesson or lecture outside of classwork that focuses on systematic racism and abuse, it’s started by some variation of ‘We are so lucky to get to be talking about this here in Seattle. Back in (other location) we would never be allowed to do this.’

I have not met a student who feels humbled by this. I have not met a student who heard this and thought ‘Wow, I’m so privileged to get to learn about the different experiences that the student right next to me goes through.’

Instead, I worry that this sort of introduction starts us off with a feeling of superiority like we’re better than other people for talking about race. When we have the mindset that Seattle itself is ‘antiracist’, we apply that to ourselves and thus feel less responsible.

Not only is a lack of responsibility preventing us from educating ourselves on racism, but it is also allowing people to continue encouraging racism. “They [perpetrators of racial abuse] just get warning after warning and no punishment so they don’t take it seriously.”

When there aren’t any real consequences, it makes those harmful actions seem insignificant, and racism is anything but. These sorts of interactions range from blatant racism to ignorant comments, but one student says the majority of the racism that they have seen in Seattle is “Where white people have positive intentions but negative impacts because they’ll say these racially insensitive things and without recognizing the situation.”

Telling someone that they are ‘so exotic!’ may seem like a compliment, but doesn’t feel like one. ‘Exotic’ is a word used for fruit and birds, who typically have unusual colors or features. People are not fruits that have been shipped from far off countries to be enjoyed in the luxury of your home. People are not birds to be stared at and examined. When positive intentions clash with negative impacts, change has trouble following.

There is something noticeably wrong with our curriculum. A white student said that “In the history classes I’ve [noticed that] they don’t focus much on Asia and the Middle East and more on Europe and American [history].”

Another student, who is white and Filipino, was shocked at how long it took SPS curriculum to acknowledge that “Christopher Columbus was a very bad person.”

In response to this, they said “I don’t think kids should have to wait until adults think it’s palatable for them before they learn about authentic history. We don’t have a censor.”

They told me that they understand why schools shouldn’t go into graphic detail, but it’s still possible for us to teach children about the horrors of colonization before they understand what it means. This student also mentioned how a “euro-centric” education doesn’t treat racism like a current-day issue.

The system we have now is messed up: there’s no denying this. A white staff member at Lincoln said that “We live in a society that is racist in many ways, and as staff members, we constantly need to work to undo the way that racism has shaped the way that we perceive the world and the way that we teach.”

Another white student said that “When the current admin came into power, the system was already so [messed] up and the system was so stacked against being inclusive.”

Our country was built on centuries of extreme racism, and reversing some of the harms is going to take a while. An Asian and white student told me that they “understand they [administration and the district] are also trying to accommodate people who feel guilty or defensive in conversations about race.”

However, this doesn’t justify any potential wrongdoing. “…if admin were acting with integrity, they would still do the right thing to accurately educate their students. I know these social pressures are not absolved by my morality.” To this student, it appears as if the wants of white guilt are coming before the needs of racial justice.

It isn’t just them. Donald Earl Collins, the author of “Black” America: Multiculturalism and the African American Experience (2004) and an opinion writer for Al Jazeera, wrote in an article called ‘Racism never left US schools — now it’s taking worrying new forms’ about how backlash from scared parents can cause school administration to censor our education just because it’s hard for parents and schools to accept how their own privilege.

There is a varied understanding of white guilt. Some people view it as taking the blame for horrible things white people did in the past. This is difficult to approach because perpetrators of racial abuse are present in nearly every white person’s family history.

Because of this history of abuse, the effects of racism are still heavily felt by people of color, while white people sometimes don’t understand what the big deal is. Some people view white guilt as the compulsory shame for being born the ‘right’ race.

Having society set up to accommodate you may not be something you grow up aware of, but when you find out, that can’t feel great.

The response to white guilt also varies from person to person. Peggy McIntosh, a scholar, wrote an article in 1989 noting her newfound perspective on white guilt. “I began to understand why we [white people] are justly seen as oppressive, even when we don’t see ourselves that way.

I began to count how I enjoy unearned skin privilege and have been conditioned into oblivion about its existence.” she states, noting that she felt that, “…whites are carefully taught not to recognize white privilege.”

She strongly believes that her ignorance is the result of a society geared towards “obliviousness”.

This article identifies a problem, but what’s the next move? In the crudest way possible? That’s not my job. It is not the responsibility of the person of color to educate the many white people in their lives about all of their advantages.

Despite this, we can be seen as representatives of our race, and most of us try our hardest to be truthful. I read (and write) news articles on racism to have a better understanding of what society wants from me.

My friends sit through history lessons that encourage bigotry. Numerous students were sad when one of our Asian teachers, who made us feel less alone, went on leave. Between classes, students tell each other about questionable comments made by the teacher or other students.

It is not a person of color’s job to educate people on privilege, nor is it their responsibility to ‘fix’ the racism seen every day, but that doesn’t stop so many of us from trying.

My advice is to listen and learn. Use empathy before anger. Find reliable sources before defending your opinion. It’s okay to be wrong, and it’s okay to let someone else be right.

We’ve all come so far, and we’re not done yet.